A Tavern with Many Names

In each era, it seems there's always that one tavern where some rather unsavory activities take place. Enter Ames Tavern, or as it would later be known, Foster, Mayo, Ward, Eagle, and Elm Tavern. Perhaps they thought changing the name would do the trick?

Ye Ames Tavern

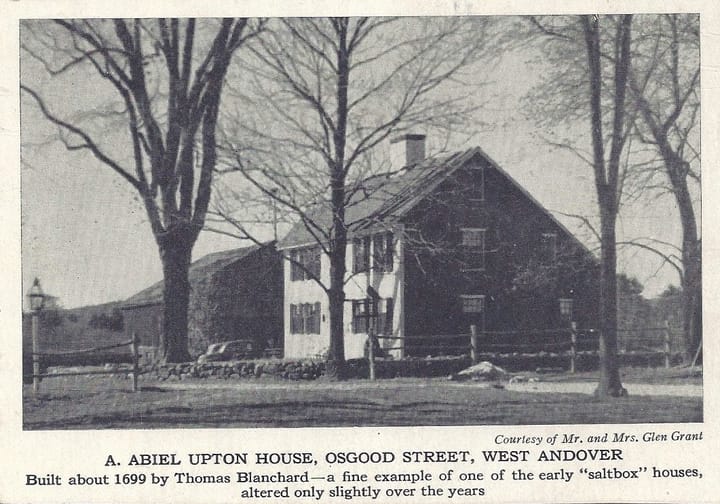

Let's dive into the history of Ye Ames Tavern. Benjamin Ames, born on November 9, 1749, was the son of Captain Benjamin Ames, who led Salem Poor's company at the Battle of Bunker Hill, and Hepzibah Chandler, the great-great-granddaughter of William Chandler, the owner of Horseshoe Tavern. In April of 1772, Ames tied the knot with Phebe Chandler, a distant cousin. Sometime in the late 18th century, they decided to open "Ye Ames Tavern." You might recall Phebe Chandler as the daughter of William Chandler, the owner of our very own Horseshoe Tavern and an accuser in the Salem Witch Trials. The name continued to hold significance, lasting 74 years after the birth of the first Phebe Chandler and spanning three generations. It's yet another example of tavern ownership running in the family, particularly on the female side.

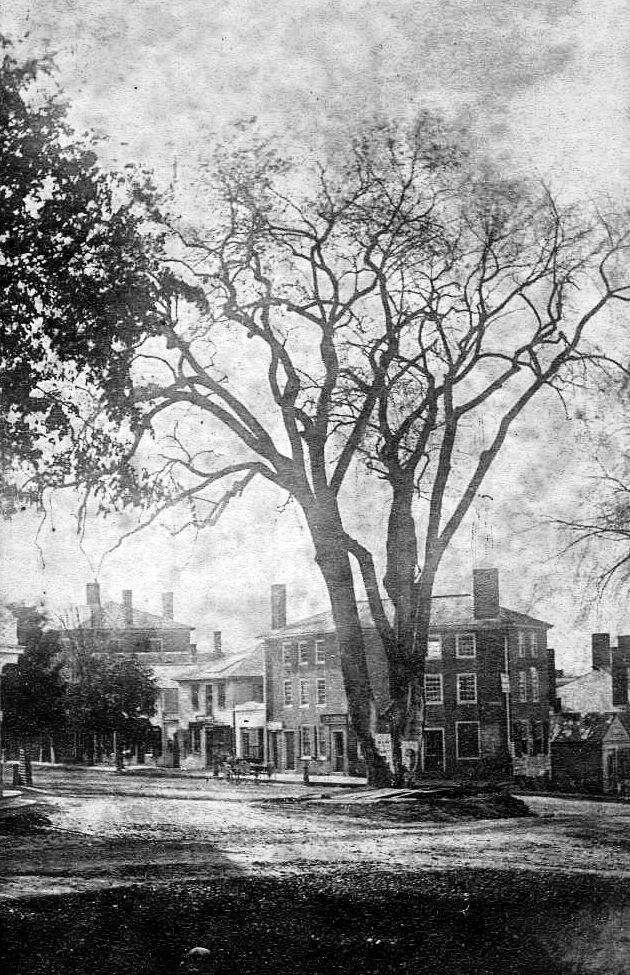

This tavern was strategically built along what would eventually become Main Street in Andover. Its location was ideal, sitting at a convenient distance from North and South Parish, making it accessible to both communities. It also anticipated increased traffic due to its position on the route leading to the ferry crossing over the Merrimack River to Haverhill. The Poor Tavern was just 2.8 miles to the north, making Ames’ tavern a convenient stop for travelers from both the north-south and east-west directions.

Tavern ownership underwent significant changes over the years. In the 17th century, taverns primarily served as social and business hubs for the local population. With the improvement of roads and increased travel, especially via stagecoaches by the end of the 18th century, taverns evolved into inns or restaurants. Their buildings grew in size to accommodate larger crowds, particularly those traveling by stagecoach. After the Revolutionary War, money was tight, and the production of rum significantly decreased. Cider, punch, beer, and wine were still readily available and often consumed in excess, but the population was still recovering from the costly and emotionally taxing war. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts introduced new rules, somewhat similar to the previous ones, but now including regulations against gambling and other activities. I am sure they were not rigorously followed.

Benjamin Ames, as was the custom, built a house and lived in the rear of the tavern. Livery stables were constructed along Main Street. It seems that Ames had a lot of misfortune. His wife died in 1798, his father who owned the land, died two years later. The tavern, which was one-third of a mile from the Abbot Tavern was “never a paying venture” and it is recorded that “his son Ezra Chandler Ames helped his father in the Ames Tavern until he was of age”. Ames mortgaged other real estate properties to keep the inn afloat before his sudden death in the tavern on November 24, 1813. His son sold the tavern to William Foster on August 16, 1816.

Following the common practice of the time, Benjamin Ames built a house and lived in the rear of the tavern. Livery stables were constructed along Main Street, reflecting the bustling activity of the era. Unfortunately, Ames faced his fair share of misfortune. In 1798, his wife passed away, and just two years later, his father, who owned the land, also passed away.

The Ames Tavern, situated about a third of a mile from the Abbot Tavern, didn't seem to bring much financial success. Historical records indicate that it was "never a paying venture." During this period, Benjamin's son, Ezra Chandler Ames, lent a hand at the Ames Tavern until he reached adulthood. Ames even had to mortgage other real estate properties to keep the inn operational.

Tragically, Benjamin Ames met an untimely end within the walls of the tavern on November 24, 1813. Following his passing, his son sold the tavern to William Foster on August 16, 1816.

Foster’s Tavern

Captain Thomas Chandler Foster, who was both the nephew and adopted son of William Foster, took ownership of the inn in 1815. It was then rebranded as "Foster’s Tavern" and remained under this name until 1825. Once again, the Chandlers found themselves involved in tavern ownership, and this time, it came with a fair share of questionable activities.

Now, as for the state of accommodations at Foster’s Tavern, they weren't exactly top-notch. Even Marquis de Chastellux, a war hero who traveled and documented his adventures in America, didn't have glowing words for the inn where he stayed. In fact, he had this to say: 'Une mauvaise auberge tenue par un homme nommé Foster: nous nous contentâmes de faire repaître nos chevaux dans ce mauvais cabaret,' which translates to, 'A wretched inn kept by a man named Foster. We were glad to do no more than feed our horses in this miserable tavern.'

Alcohol seemed to flow freely at Foster’s Tavern, and there are accounts to prove it. David Holt Jr., along with his partner, Isaac Osgood Jr., owned a successful retail grocery and dry goods store nearby. Holt was once cited for 'excessive drinking and idleness' following his time at Foster’s. But that's not all – the partners faced accusations of smuggling goods, which prompted a visit from a Customs House officer. This officer seized the suspected goods and placed them in the parlor of Foster’s Tavern.

Here's where the story takes a dramatic turn. While the customs officer was watching over the seized goods, he found himself unexpectedly trapped under a feather bed by landlord Foster. With the officer shouting, 'let me up,' he was bound, blindfolded, and 'hustled into a cart.' He was then driven for two miles to a dam along the Merrimack River and tied to a rail fence. Fortunately, he managed to seek help from some locals, who came to his rescue.

The following day, the official returned to Foster’s to investigate the incident. He found a surprisingly sympathetic landlord, Foster, who was quite vocal in his anger at what he saw as a highhanded outrage against a guest of his. However, both Holt and Osgood had vanished along with the disputed goods. The entire matter was hushed up, and the goods were eventually found.

In later years, Mr. Foster proudly recounted the events, boasting, 'We got up a magnificent supper in the hall over the brick store [referring to Holt and Osgood’s]. The punch flowed freely, and all the Andover magnates and deacons got uncommonly jolly.' It seems they must have had quite the celebration after successfully outwitting the Customs House officer.

Mayo’s /Ward/ Eagle Tavern

In 1825, Captain Foster decided to sell the establishment, and the new owner, Aaron Davis Mayo, promptly changed its name to “Mayo’s Tavern.” However, Mayo's tenure as owner didn't prove to be successful, and by 1830, the property ended up in the hands of Merrill Pettingill and Hoyt, who were auctioneers at the time.

On October 20, 1832, the tavern found a new owner in Jonathan W. Ward, who was an innholder. Under his ownership, it became known as "Ward's Tavern." Unfortunately, Ward's venture was relatively short-lived, and he eventually passed the deed to John Pearson. Pearson, along with others, later sold both the property and the tavern back to the Foster family on December 5, 1835. The hotel then underwent another name change, this time to the "Eagle Hotel." At this point, Thomas C. Foster became the proprietor, followed by Edward S. Merrill before 1850.

Full rail service to Boston, which began in 1848, brought both blessings and challenges. While the faster rail service was a welcome development, it also spelled the end of the stagecoach era, effectively bypassing Andover and leaving the inn without its usual patrons. Moreover, city dwellers now expected more upscale accommodations, as illustrated in this advertisement from August 18, 1855:

'Eagle Hotel, Andover, Mass. This place has recently undergone extensive repairs and renovations and is now eagerly welcoming the public. Inside, we have a Spacious Oyster Saloon, thoughtfully designed for the comfort of both Ladies and Gentlemen, where we serve Oysters and Ice Cream in a variety of styles. What's more, we offer a generously sized Billiard Hall, featuring three top-quality slate tables crafted by one of Boston's finest manufacturers. As the proprietor, I'm fully committed to providing exceptional service and meeting the needs of our valued customers. I look forward to having the privilege of earning your patronage – G. H. Mellen.'

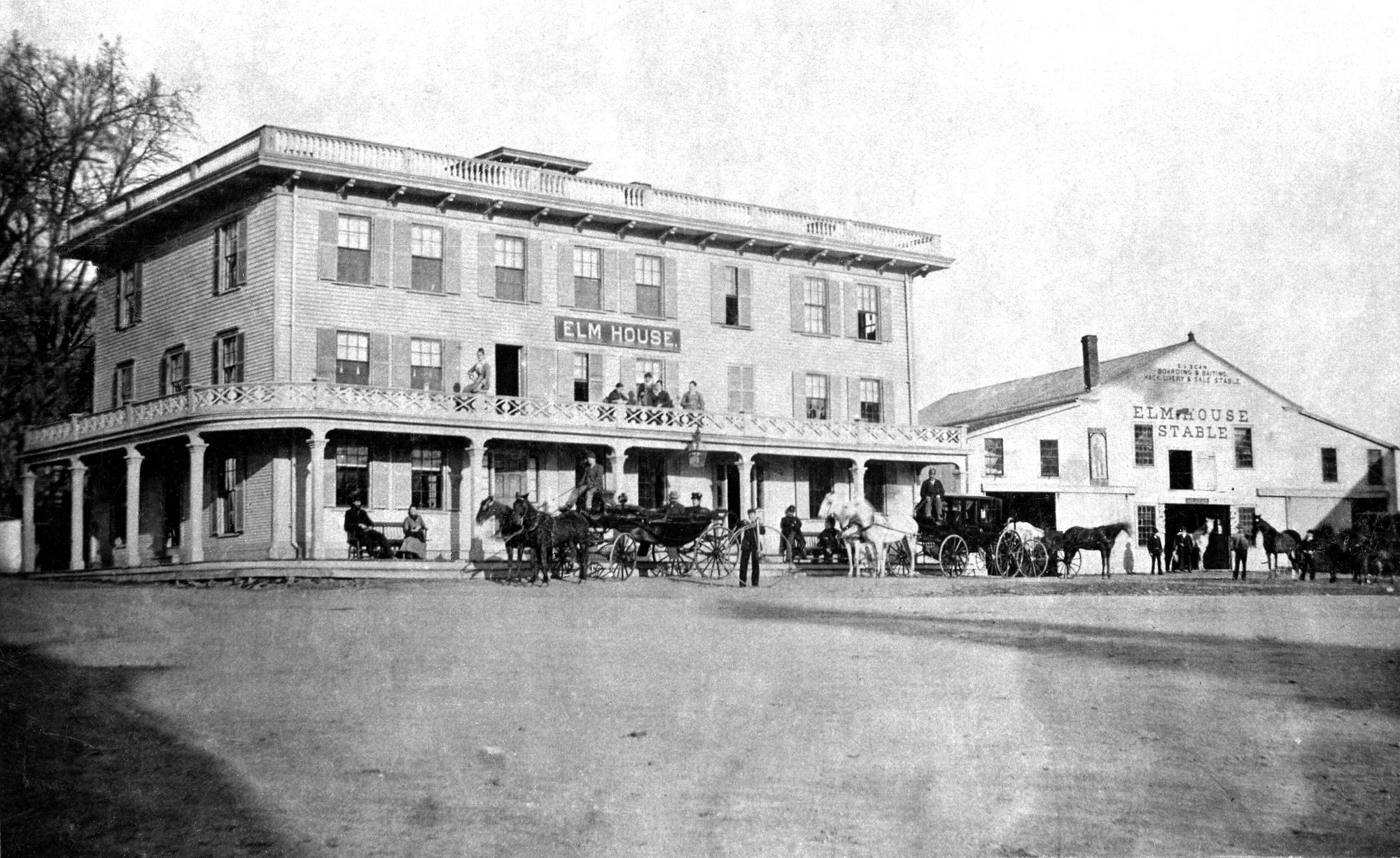

The Elm House: A Tale of Prosperity and Farewell

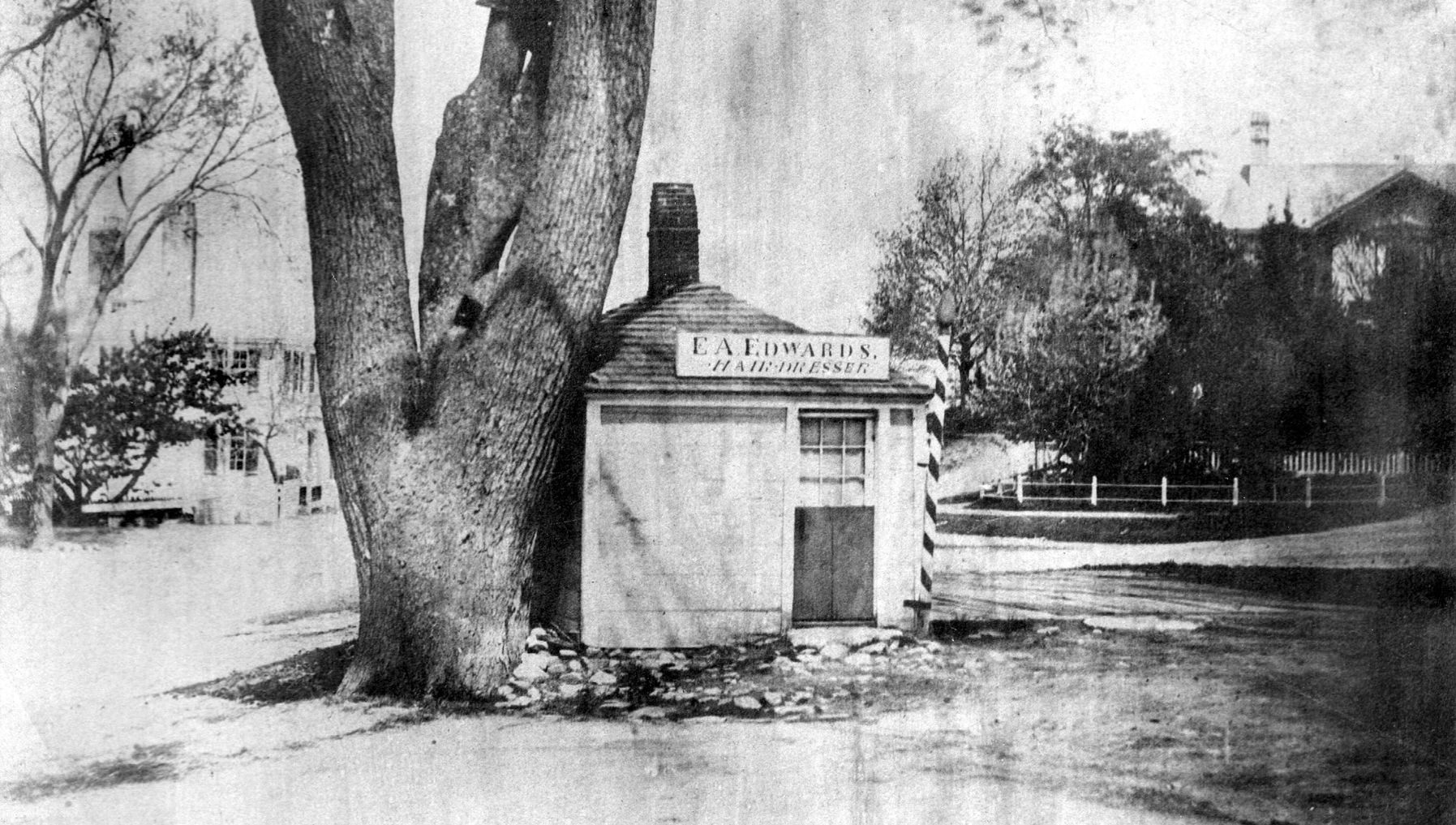

The Elm House saw both prosperity and its eventual end. It all began when Uncle Sam Bean took ownership and bestowed upon it the name "Elm House." Under Sam Bean’s astute management, the inn underwent significant changes. The old gable roof was replaced, and a full third story was added, complete with a flat roof and a charming lantern cupola. In the images below, you can see Mr. Bean proudly displaying his livery business, showcasing a variety of carriages available for hire.

The Beans, first Samuel G. Bean and later his son George Bean, managed the Elm House for several years. An advertisement from December 7, 1866, reads, 'Sleighs, Sleighs – A good assortment of new sleighs of the latest style, for sale at Elm House Stable – Motto “Quick sales and small profits” G. H. Bean.' On July 1, 1870, it was reported that John Cornell sold his horse and carriages for letting to George H. Bean, who would continue running the Elm House Stable. After George's passing, Uncle Sam once again took charge and conducted a thriving business until the late 1880s. Uncle Sam was quite the character; in addition to running the hotel, he also worked as an auctioneer and stable keeper. He was a skilled reinsman and, wearing his iconic white plug hat, and weighing 300 lbs., made quite an impression while driving his tallyho with a team of four horses.

A significant part of the Elm House's financial success during Uncle Sam Bean's tenure was attributed to the Elm House Stables, which became more famous than the inn itself. This boarding and livery stable had few rivals in towns across Massachusetts. It was impeccably appointed in every aspect, supplying vehicles for every imaginable occasion. During the summertime, especially on Sunday afternoons, getting a rental carriage was a challenge unless you had made reservations days in advance. Bostonians would arrive in Andover via the Boston & Maine Railroad and hire a buggy for the day, while locals would leave their horse and wagon at the stables before heading to Boston for shopping or business, later returning to pay for feed and care. Finally, the tavern was turning a good profit, nearly a century after its establishment.

The passing of the Elm House marked the end of an era in Andover Square, robbing it of an atmosphere that was quintessentially New England. The village green, extending from the front of the old inn to the highway, vanished. This green had been a gathering place for late-night festivities for decades, with plans often hatched for midnight bonfires on July Fourth. It was also where the Boys in Blue fired their sunrise salute year after year on Independence Day.

One particularly memorable Fourth of July morning in 1892 stands out in the recollections of Mr. George Christie. He was a boarder at the Elm House at the time, and he vividly recalled being awakened by the resounding boom of a cannon. It was July Fourth, and the Grand Army veterans were firing a salute. Despite the customary number of rounds fired right under his window, he was so exhausted and sleepy that he only heard that initial shot. On occasions, there were fights between the 'Villagers' and 'Townies' staged 'the night before' on the village green, often involving overripe eggs as ammunition.

In its later days, the Elm House became a boarding house. In 1894, it was demolished to make way for a new building, a sign of progress marking the end of an era.

Sources

Andover Historic Preservation Site, many write-ups from Elm Square, Welcome to the Andover Historic Preservation Web Site | Andover Historic Preservation (mhl.org)

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1880.

Helmers, Marilyn, From the History Buzz Archives: An Update on the Andover-Wilmington Railroad, Andover Center for History and Culture, September 2020.

Ralston, Gail, Smuggling in old Andover, The Townsman, Andover, January 21, 2021.

Stowe, Hariett Beacher, Oldtown Folks, available in public domain by LibriVox, 1869.

Comments ()