Chandler's Tavern - Part 1

In 1658, an intriguing chapter began in the life of William Chandler, the son of a humble immigrant and future tavern owner. At the age of 22, he became a landowner in Andover, and not only that, but he also worked as a skilled brickmaker. During this time, he found love and married Mary Dane, the daughter of his stepbrother Francis Dane. Their union marked the beginning of a growing family, as they welcomed their first child, Mary, in 1659, followed by William in 1661. I can only imagine the amusing challenge of calling a name and having multiple little ones respond. Interestingly, their next children were named Sarah and Thomas, the same name as William's older brother.

William Chandler's original house lot was conveniently located next to his brother-in-law and his own brother on the town green. As the town expanded, the early settlers continued to acquire more land through division or allocations, and William was no exception. In total, he accumulated four portions of land. Each house lot came with a combination of upland, meadows, and swamp land, commensurate with the original allocation. For instance, William's 4-acre house lot came with 4 acres of upland and 6 acres of meadow. The clustering of these house lots provided both protection and practicality, with uplands for timber and meadows for cultivating crops. It ensured that each family had sufficient land to sustain themselves. Notably, William was fortunate enough to secure the claypits for one of his allocations, which he utilized for making his bricks. In 1662, the fourth and final division of land occurred, resulting in the owner of a 4-acre house lot, like William, ultimately possessing 122 acres. Meanwhile, the house lot of 20 acres, granted over time, grew to a substantial 610 acres.

With his marriage to Mary Dane in 1658, William Chandler built a modest home adjacent to his relatives. His life was bustling with the joys and responsibilities of raising a large family, tending to his trade as a brickmaker, and maintaining close connections. However, after twenty years of marriage, tragedy struck on May 10th, 1679. Mary, William's beloved wife, passed away while giving birth to their son, Joseph, who also tragically did not survive. Mary had given birth to a total of 11 children, with seven of them still alive at the time of her untimely death. Among them, the eldest, Mary, was just 20 years old and still resided at home.

Only five months after the heartbreaking loss, in October of the same year, William found solace in the companionship of Bridget Henchman, hailing from Chelmsford, the neighboring town to the west. Bridget, who had previously been married to James Richardson in 1660 and had a son named Thomas Richardson, became William's second wife. This speedy marriage might raise eyebrows even in the 1600s, leaving us to wonder about the reasons behind it.

A couple of years later, in need of a larger home, a significant event took place in July of 1683. William Chandler and Joseph Ballard engaged in a land trade that benefited both parties involved. William acquired land adjacent to his existing holdings, while Ballard obtained land closer to the Shawsheen River. It's worth noting that the Ballard brothers were instrumental in developing the Shawsheen River area with mills, while William had the advantage of having claypits located south of his property. The Ballard mill complex was considered one of the largest of its time and is now call Ballardvale. The trade proved advantageous for everyone involved.

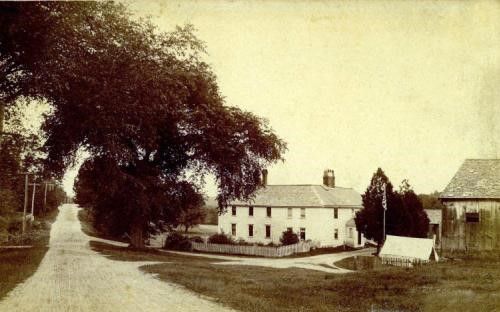

The acquisition of the Ballard property marked a significant turning point in William Chandler's life. His new home, located on Milk Street just off the Way to Ipswich/Billerica, quickly became a bustling hub of activity. It was a place where children played, family members gathered, neighbors socialized, and even weary travelers sought respite.

During that time, streets were not named in the conventional manner we know today. Instead, they were identified by their direction, such as the Way to Boston or the Way to Billerica. As for houses, they lacked numerical addresses and were simply known by the names of their occupants. This naming convention helped people navigate the town and locate specific destinations.

Given that many individuals struggled with reading, signs played a vital role in guiding visitors. A sign like the Horseshoe, bearing the name of Chandler's tavern, might have been mounted on a hanging board. The sign could have featured a painted or carved depiction of a horseshoe, serving as a recognizable marker for Chandler's establishment.

Imagine the scene—a vibrant home on Milk Street, just off the Way to Ipswich/Billerica, adorned with a distinctive sign, inviting both locals and travelers alike. The Chandler household, bustling with activity and welcoming to all, contributed to the rich tapestry of the town's social fabric during those times.

First Liquor License

By law, every town needed to have an Ordinary as a place to do business, hear local news and meet-up for both pleasure and militia drills. Ordinary keepers had a lot of legislation – the license, cost of beer, malt content and alcohol content. In the 1651 law it said that a hogshead of beer had to contain six bushels of malt to sell a 3d. a quart; four bushels to sell at 2d., and two bushels to sell at 1d. To maximize profits, keepers would frequently dilute their beer. It seems that not a single brewer in seventeenth century Essex County received a fine for diluting his beer or illegally brewing with Indian corn, oats, or rye.

Mr. Edmond Faulkner, who negotiated with the Native Americans to "buy" Andover in 1646, holds the distinction of being the town's first licensed vintner (1648). During that time, a vintner was similar to a modern liquor store, specializing in the sale of strong liquors. According to the Faulkner family legend, Edmond Faulkner offered rum to the Native Americans to "assist" the negotiations. The entire story of procuring the Andover land, which cost £6 and a coat, raises thought-provoking questions about the relationships between Native Americans and settlers in the 1640s.

In 1644, Passaconaway, the leader of the Pennacook Confederacy, including the local Pawtucket band, agreed to a treaty of submission after his son was held captive for two years. Massachusetts Court records indicate that the sale was negotiated by Cutshamache, the Massachusetts Sagamore, but his band resided south of Boston. The entire process of "buying" Andover appears dubious.

Adding to the suspicious circumstances surrounding the trade, the first fully recorded history of rum in the Americas dates back to 1650, making it unlikely that Faulkner had access to rum as early as 1646. This family legend remains historically uncertain at best, but it does provide some insight into Faulkner's character and actions.

It's unclear exactly what transpired, but within a span of five short years, Faulkner's business ventures came to an end, and Andover faced penalties for lacking an "ordinary." In the following year, a new vintner emerged in the form of Deacon John Frye. While we don't have specific details about Frye's offerings, it's likely that he sold popular beverages of the time such as cider, beer, and rum.

During this period, Andover's prominent figure, Simon Bradstreet, engaged in trade with Barbados. His sawmill provided lumber for southern destinations, while sugar, molasses, and rum made their way northward. This trade network added to the town's economic activity and contributed to the availability of various commodities.

John Frye played several significant roles in the early years of Andover. As the Church of Andover was organized on October 24, 1645, Frye was among the ten freeholders required for its establishment. Both John Frye and his son, John, went on to serve as Deacons in the church. Once again, a highly respected individual from the North End of town was entrusted with the responsibility of obtaining a license for selling alcoholic beverages, highlighting their standing within the community.

Chandler gets a license.

It was common for homes to charge travelers and neighbors for drinks before getting a license. For example, in 1680 John King of Salem expressed surprise at being indictment because he believed that “the approbation of forty or fifty of the neighborhood to sell liquor by retail” was sufficient license. For three years, backed by local custom, he “supposed he was at liberty to supply the necessities of the neighborhood.” This is likely how William Chandler’s Horseshoe Ordinary began.

Any tavern needs a few things to be successful – a welcome and friendly environment, convenient location, a sign, and good drink. The Chandler home was on a well-traveled road, with many travelers stopping randomly looking for rest and beverage. The established ordinaries were 1-1/2 miles walk away; Chandler's tavern offered a more convenient stop for travelers. And let's not forget a good drink. That would have been Bridget's job to make the beer or cider that encouraged repeat customers.

Moreover, Chandler's home was strategically situated near the South End residents, who represented a distinct social group compared to the North Enders. In the South End, Scots and other newcomers were forging bonds and forming marriages, thereby creating a unique community and social structure separate from the North Enders. It's not uncommon for towns to have neighborhoods that are perceived as nicer than others, and in Andover, the North End held that distinction. Until Chandler's petition, all liquor licenses had been concentrated in the North End for the past 40 years. However, Chandler's actions changed that, at least for a year.

In the subsequent year of 1687, an intriguing turn of events unfolded as William Chandler found himself facing a complaint filed by none other than Capt. John Osgood, a respected figure in the North End of town. Osgood, an innkeeper, leader of the local militia, and a prominent member of the community, accused Chandler of unlawfully selling cider and other strong drinks without a valid license from his own dwelling.

Faced with this accusation, Chandler promptly presented his defense, producing the expired license that had been previously granted to him. Recognizing his error and the gravity of the situation, on September 14, 1687, William Chandler humbly approached the "Majesty’s honoured Court of Sessions for the County of Essex" to seek the renewal of his license.

In his sincere plea, Chandler expressed his genuine desire to maintain a public house of entertainment, emphasizing the pressing need to address the concerns raised by travelers who had lamented the absence of a suitable establishment along the road leading from Ipswich to Billerica. Furthermore, Chandler shared his personal predicament, say he was unable to pay the license fee due to a fine imposed upon him in Salem.

With utmost humility, Chandler presented these compelling reasons as grounds for the renewal of his license, hoping for a favorable outcome from the esteemed Court. To strengthen his case, Chandler obtained a letter of support from his brother, Thomas, as well as four neighbors, who urged the Court to grant the license. They attested that they had often “heard strangers much complain that there is no publick house of entertainment upon the Rode, but they must goe a mile and a elfe out of there way." Clearly, with Capt. Osgood lodging a complaint against him and Chandler struggling to pay his fine, the support from his neighbors was greatly appreciated. (Chandler was fined for his wife having a silk scarf, which was frond upon. We don't know if this is the fine, he is referring to, or another, but it is clear that he needs the income from his tavern.)

The story of early days of William Chandler's tavern exemplifies the complex dynamics of the time, where competition between taverns, social divisions, the network of relationships, and the necessity of licenses shaped the landscape in Andover. It serves as a reminder of how individuals navigated the challenges of running a business and seeking approval from the authorities while also relying on the support and goodwill of their neighbors. It is also an indicator of events to come. In part 2 of the Horseshoe tavern, we will explore how Chandler is faced with new complaints, and the first murder in town.

Sources

Abbot, Elinor, “Transformation: The Reconstruction of Social Hierarchy in Early Colonial Andover, Massachusetts”, 1989

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, Boston, 1880

Philip J. Greven, Jr. Four Generations: Population, Land and Family in Colonial Andover, Massachusetts

Wrightson, “Alehouses,” Essex Records, VII, 109, 251; VIII,46

Comments ()