Colonial Christmas drinks

Puritans and the 1600’s

The Puritans held the belief that birthday celebrations, even for Jesus Christ, were not appropriate. According to a law passed in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1659 to 1681, “whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way” would face a five-shilling fine. (It wasn't until 1870 that U.S. Congress officially recognized Christmas as a holiday.)

Despite the Puritan stance, many colonists in New England did celebrate Christmas, although these gatherings weren't exactly family-friendly. In 1662, a man from Beverly, Massachusetts, found himself in court for hosting a rowdy Christmas Day event. He had a reputation as a troublemaker, and his family frequently clashed with Puritan society.

During the 17th century, it was common to enjoy wine, punch, and homemade brandies to mark the twelve days of Christmas (from December 25th to January 6th). However, in 1687, the Puritan minister Increase Mather strongly criticized Christmas celebrations. He asserted that those who partook in the festivities "are consumed in compotations, in interludes, in playing at cards, in revellings, in excess of wine, in mad mirth."

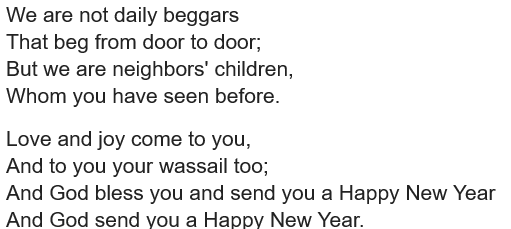

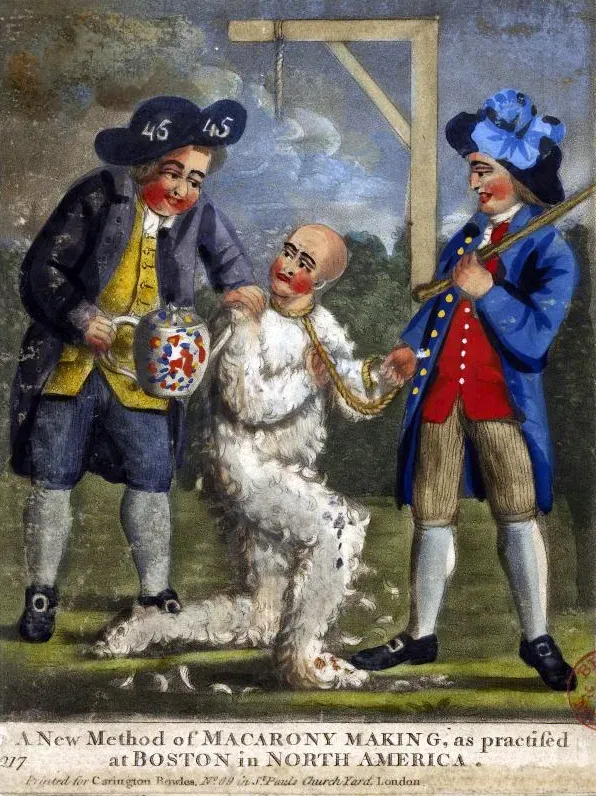

Mumming and Wassailing

During the Christmas season and around the last day of the twelve days of Christmas (January 6), people found joy in various festivities such as drinking, feasting, mumming, and wassailing. Mumming, also known as "masking," involved individuals, often those less fortunate, dressing up in costumes and going from house to house, staging plays, and engaging in other performances. Wassailers, on the other hand, would travel among the homes of wealthier citizens, sharing warm, spiced ale or mulled wine while singing together.

These customs might bring to mind the spirit of trick-or-treating during Halloween, albeit with adults and, unfortunately, sometimes leading to violence.

One notable incident of Christmas mayhem took place on Christmas Day in 1679 in Salem, Massachusetts. Four men, eager for some holiday spirits, heard that 72-year-old John Rowden had crafted perry, a liquor made from pears. So, they decided to make an unplanned visit. This particular form of wassailing turned out to cause more trouble than merriment.

In the late seventeenth century, a commentator remarked, "Wenches ... by their Wassels at New-years-tide ... present you with a Cup, and you must drink of the slabby stuff; but the meaning is, you must give them Moneys." This highlights the tradition of offering wassails as a way to receive monetary gifts during the New Year's celebration.

In 1712, Boston's Cotton Mather wrote, "Feast of Christ's Nativity is spent in Reveling, Dicing, Carding, Masking, and in all Licentious Liberty...by Mad Mirth, by long eating, by hard Drinking, by lewd Gaming, by rude Reveling...." Even Christmas caroling did not escape criticism, as it was associated with these other objectionable activities.

Since Christmas was treated like any ordinary day, it's reasonable to assume that local establishments, especially taverns maintained their usual level of business. Most likely, they served beer, cider, and increasingly popular rum during this period. Taverns, following their customary practices, likely promoted the day to attract more patrons. Establishments like William Chandler's Horseshoe Tavern were known for encouraging toasts, games, and various activities to boost their business. Some Massachusetts towns, including Marblehead, gained a reputation for hosting particularly lively celebrations, despite officials' persistent efforts to suppress Christmas observance throughout the colony.

Replicating Old Recipes

I wholeheartedly encourage you to try out the recipes featured in this blog. However, if you're aiming to capture the authentic taste of the original recipes, let me share a few pieces of advice: Make it to your liking, and find joy in it if it brings you satisfaction.

It's fascinating to note that the first American printed cookbook didn't appear until 1796. There were cookbooks before that, but most people relied on family and friends for culinary knowledge, making recipes incredibly personal and subject to modifications across generations. For instance, when a recipe called for a cup of something, it literally meant a teacup. But let's be real—do all of your teacups measure the same?

Furthermore, the ingredients themselves had distinct flavors compared to what we're accustomed to today. For example:

- Milk was straight from the cow, with the heaviest cream reserved for butter. The remaining milk was unpasteurized, and it likely resembled modern whipping cream.

- Apple cider was more like the English or French variety, akin to a dry white wine, not the sweet canned hard cider we have today. You might find similar ciders in a quality wine store.

- Rum, the preferred alcohol, differed significantly from the refined version we enjoy now. During this era, it was a rougher, darker spirit that often needed additional ingredients to enhance its taste.

Drink recipes were often associated with specific taverns, and these specialty concoctions were guarded as trade secrets. So, especially when it comes to drink recipes, they were frequently based on taste and evolved over time.

Punch was the go-to-choice for sharing drinks and toasting to good health, especially during the New Year. Alongside beer, cider, and wine, punch recipes were likely crowd favorites during the 1600s. So, dive into these historical recipes, make them your own, and savor the unique flavors of the past! Cheers!

"WASSAIL" or Christmas Punch (serves 40)

- 1 gallon heated apple cider [hard dry cider is preferred]

- 1 ounce brandy

- 1/2 quart light rum

- 3 sticks cinnamon

- 3 to 6 whole oranges

- small bag of whole cloves

1. Simmer mixture with 3 sticks whole cinnamon to melt--DO NOT COOK.

2. Allow to cool, pour into punch bowl.

3. Separately stick whole cloves around entire surface of 3 to 6 whole oranges. Let me assure you, this is a lot of cloves and can be very expensive. So consider, using a smaller amount for decorating the oranges and adding a bag of cloves to simmer with the cinnamon in the mixture.

4. Place oranges into baking pan with 1/2 inch of water and bake at 350° for 45 minutes.

5. Place oranges into punch bowl

Christmas drinks in the 1700s

During the 1700s, wassailing remained a common tradition, but the New England colonial Christmas tradition had a significant impact, maintaining the perspective that Christmas was just another ordinary day for much of the colonies. An illustration of this mindset is evident in 1789 when Congress held a session on Christmas Day, businesses in New England were open, and children attended school on Christmas, persisting well into the 1800s.

The New England region, in particular, embraced the "just another day" attitude, as captured by John Adams in his December 25, 1765 diary entry: "At Home. Thinking, reading, searching, concerning Taxation without Consent, concerning the great Pause and Rest in Business... Went not to Christmas. Dined at Home. Drank Tea at Grandfather Quincys [Abigail’s parents] ... Spent the Evening at Home, with my Partner and no other Company." Despite his daily glass of hard cider, Adams was not a big drinker and stuck to a cup of tea on this day.

In contrast, other colonies celebrated with more gusto, often firing muskets and cannons. Both Thomas Jefferson and George Washington marked the day in their diaries, with Jefferson describing it as a time of "greatest mirth and jollity" as early as 1762. The Twelve Days of Christmas were observed, and Washington, for instance, chose January 6, the twelfth day, for his wedding to Martha. Washington even engaged in fox hunts, a common festive activity in Virginia during that time of the year.

When it came to drinks, Washington favored port and Madeira wine on Christmas, Adams stuck to his tea, and Benjamin Franklin noted toasting with a glass of wine to one's health. Each had their own way of celebrating the season, reflecting the diverse traditions that shaped the festive landscape of the 1700s.

Eggnog

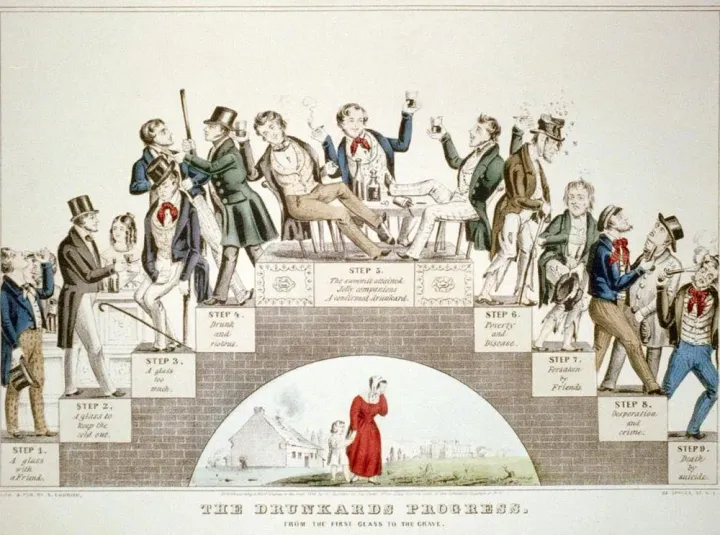

In the 1700s, taverns were renowned for crafting and featuring "specialty drinks" with charming and not-so-charming names like Rattle-Skull, Stonewall, Bogus, Blackstrap, Bombo, Mimbo, Whistle Belly, Syllabub, Sling, Toddy, and the Flip. These concoctions, often rum-based, were cleverly crafted to entice patrons. To mellow the harsh flavor of the rum, milk (cream) and eggs were commonly added to these drinks. Among them, the most beloved beverage from 1650 to 1800 was the flip (check out the blog entry: Ready to Try 17th Century Drinks), a warm ale and rum concoction featuring eggs and cream and topped with nutmeg. As soon as rum made its entrance, variations emerged, likely paving the way for what we now know as eggnog.

Eggnog became a festive tradition during the holiday season across the colonies in the 1700s. Interestingly, it wasn't always made with alcohol, and different regions tailored the recipe to suit their unique tastes. For a glimpse into the early days of eggnog, let's turn to Maria Rundell’s New System of Domestic Cookery, first published in 1805. Her "eggnog" recipe, though, requires a bit of experience to determine the exact quantities. So, if you're feeling adventurous, dive into the world of historical eggnog and savor the flavors of a bygone era! Cheers!

Old Man's Milk (or Eggnog) Recipe– a nutritious and pleasant beverage. Beat up the yolk, of an egg in a bowl or bason, and then mix with it some cream or milk, and a little sugar, according to the quantity wanted, and let them be thoroughly incorporated. A glass of spirits, or more, is to be then poured gradually into the mixture, so as to prevent the milk or cream from curdling. This mixture will be found useful to travelers who are obliged to commence their journey early, particularly if the weather be cold and damp. Sounds like a tavern recipe to me!

Here is another eggnog recipe from the Farmer's Almanac, although Mount Vernon’s librarians have reported no eggnog recipe has been definitively linked to Washington. Maybe it was just advertising for the Farmer's Almanac?

George Washington's Eggnog Recipe - One-quart cream, one-quart milk, one dozen tablespoons sugar, one-pint brandy, ½ pint rye whiskey, ½ pint Jamaica rum, ¼ pint sherry – mix liquor first, then separate yolks and whites of 12 eggs, add sugar to beaten yolks, mix well. Add milk and cream, slowly beating. Beat whites of eggs until stiff and fold slowly into mixture. Let set in cool place for several days. Taste frequently.

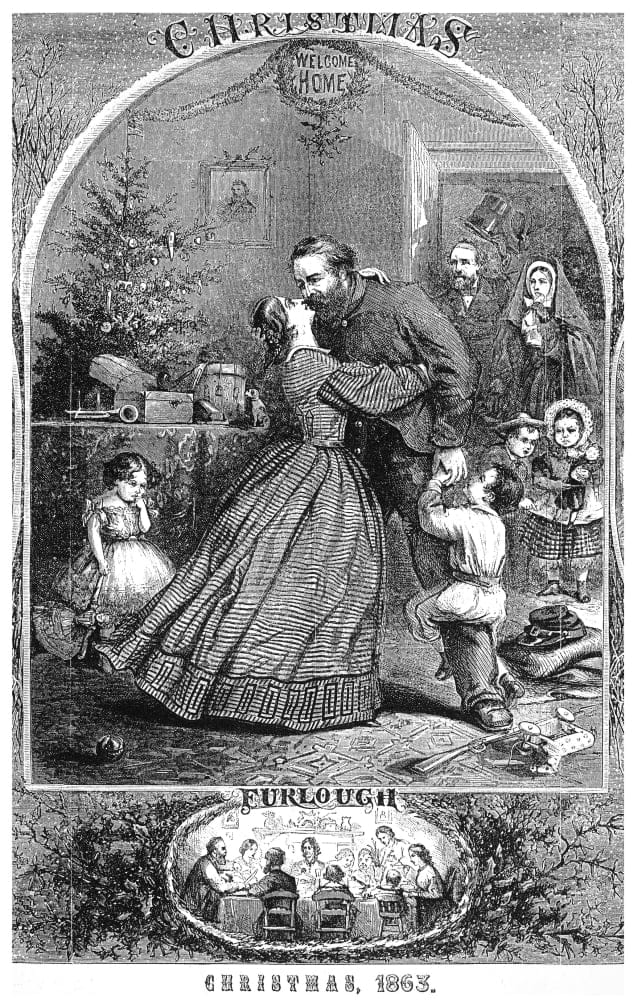

Christmas of the 1800's

In the early 1800s, the resistance from churches against celebrating Christmas began to ease. Influential works like the poem "T'was the Night Before Christmas," published in 1822, and Charles Dickens' "A Christmas Carol" in 1843 played a significant role in shaping the image of Christmas. By the mid-1800s, Thomas Nast, the renowned illustrator for Harper's Weekly, gave Santa and holiday traditions a new identity. This transformation paved the way for the Christmas we recognize today, complete with a decorated tree, Santa Claus, gift-giving, family time, and the acknowledgment of a special holiday.

Simultaneously, the 1800s saw the decline of many taverns, affected by factors such as the rise of railroads, shifting patronage trends, and changing styles. Hotels with bars and stables found favor among patrons, while the traditional tavern room at the front of the house saw dwindling numbers. Whiskey also took over as the preferred drink, ending the 150-year dominance of rum. Another notable shift during this period was the beginning of recognition for the Temperance Movement, impacting local taverns.

Despite these changes, holiday drinks continued to include mulled wine or cider, punch, and eggnog, carrying on the legacy of our past. These delightful beverages hold a special place in history, and I encourage you to try an "old" recipe to make it your seasonal tradition. Cheers to embracing the festive spirit and the rich traditions that have shaped our holiday celebrations!

Note to my readers:

I will be taking a couple of weeks off to enjoy the holidays. Please drink responsively and enjoy the celebrations of the season. Happy New Year!

Sources

Cheever, Susan, Drinking in America, Our Secret History, Twelve, New York, 2015.

Hirsch, Corin, Forgotten Drinks of Colonial New England, The History Press, Charleston, SC, 2014.

Grasse, Steven, Colonial Spirits, A Toast to Our Drunken History, Abrams Image, New York, 2016.

Murray, John, The New Family Receipt Book, London, 1822.

National Archives for Founders, Decr. 25th. 1765. Christmas. (archives.gov)

Comments ()