Post Road Connections

Early roads expanded upon Native American paths, accommodating both walking and horseback travel while gracefully maneuvering around obstacles. Enhancing and upkeeping these roads held immense significance for the town's wellbeing and trade. Unlike today, where the federal or state government funds road repairs, back then, the responsibility rested on the town's shoulders.

In those times, every male citizen was obligated to join a work party aimed at road improvements and maintenance, reflecting a collective effort to keep the roads functional. However, those with financial means could opt out by hiring a replacement worker.

In 1647, individuals appointed by the General Court undertook the task of planning the "way from Reading to Andover" and "the road from Andover to Haverhill," while also conducting a survey of the Merrimack River. This newly established north-south road marked the beginning of a series of connections that effectively positioned Andover along the route from Boston.

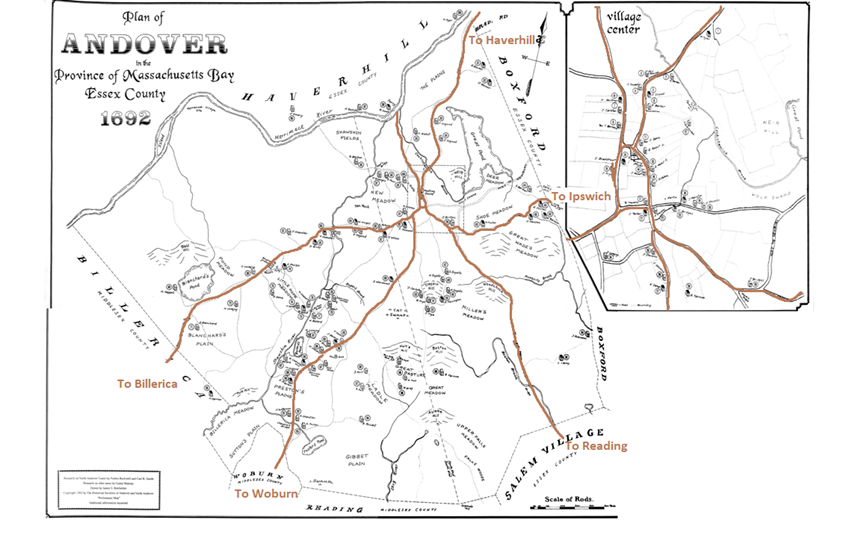

Unsurprisingly, the initial roads were oriented north-south (Haverhill – Boston), east-west (Ipswich – Billerica), and eastward (Ipswich to Salem), in addition to utilizing waterways (the Merrimack River leading to the Atlantic).

Not all roads went in smoothly. Back in 1653, there was a talk in the General Court about the road stretching from Rowley to Andover. This subject came up again in 1671, mainly because Andover had yet to follow through on the necessary improvements. These roads were quite the adventure, leading through remote forests inhabited by indigenous people and teeming with wild creatures like moose and bears. Clearing timber and making the path usable for carts demanded a considerable amount of work. However, it seems the main hurdle wasn't just the labor but the road's actual location.

Efforts were made to establish the road from Andover to Rowley and Salem. But by 1688, Andover found itself expressing its grievances to the General Court. They requested not to be burdened any further by these rocky and practically impassable paths, which posed serious risks to both people and livestock. These weren't mere inconveniences, these rough roads endangered lives and limbs.

As shown in the 1692 map above, Andover had developed several roads connecting to major commerce centers like Haverhill to the north and Boston to the south. Taverns were constructed along these new roads to accommodate travelers and facilitate trade. As time went on, roads were expanded and straightened to accommodate carriages and eventually stagecoaches. This marked the inception of the Boston to Haverhill post road.

Post Roads

The first mail service in North America began on January 22,1693 with a dispatch from Boston to New York City. This trip of over 220 miles took 14 days – approximately 15 miles per day, with a tavern stop each night. The introduction of post riders who traveled on horseback to deliver mail, run errands, facilitate communication, and handle financial transactions. They disseminated news before newspapers became prevalent. These post riders were esteemed and well-liked figures who traversed these routes. When the ride made the return trip to Boston, also in 14 days, it was considered a marvel and cause for celebration.

The post roads that started in Boston (near King Street, now Washinton Street) soon became well-traveled routes, creating pathways for exploration and connection. These routes stretched all the way from Andover/Haverhill in the northern regions to Providence, RI down south, and even reached westward to Springfield, MA. With the growth of trade and communities, roads to the bustling city of New York also gained significant importance. It's intriguing to note that the modern interstate highways we use today, like I-95 to the south, I-90 to the west, I-93 to the north, and I-91 connecting Springfield to Hartford, closely follow the trajectories of these early roads, although not exactly.

Long-haul post riders, such as those journeying from Boston to New York City, would frequently swap horses at convenient tavern stops along the way. These taverns, often thought of as "modern" in those times, offered much-needed nourishment, a place to stable horses, and a spot to rest, all while serving as hubs for sharing the latest news. I should note that a place to rest was often sharing a bed with a fellow traveler.

As we'll come to discover in the upcoming editions, these travel routes played a crucial role in facilitating communications, especially revolving around taverns and socializing, as well as aiding in the assembly of the militia. It's fascinating to consider that without these early post roads, places like Andover might have been too distant to stay informed about events in Boston following the Molasses Act. These roads also bridged taverns with their source of local rum, given that Boston boasted 38 distilleries and Haverhill contributed more to the mix. This intricate web of trade, communication, and community gathering unfolded right within the taverns situated along these early post roads.

How lengthy was the journey from Boston to Andover?

Well, road travel back then was quite a rigorous affair. If you were to hop on a horse and ride to Boston from Andover, you'd be in for a solid 9+ hours of riding time. Quite a contrast to today's 30-minute breeze (or just an hour if traffic's being tricky). While I haven't stumbled upon exact numbers for the post rider's pace, we can piece together some clues to estimate the timeframe.

Those long-haul post riders, like the legendary Paul Revere on his Boston to New York City runs, rode at quite a brisk pace, swapping horses along the way by the middle of the 1700’s was expected to travel 30 miles per day. Our Andover/Haverhill route, on the other hand, didn't require such breakneck speeds and likely didn't involve switching horses. A horse typically strolls at around 4 miles per hour and can trot at 8-12 miles per hour. Considering the 32-mile route with stops every 5 miles (which makes sense given the presence of at least 7 towns), the whole trip could easily fill up multiple days.

Jumping ahead fifty years, a stagecoach was advertised to take 9 hours for the Boston to Haverhill trip, including a horse change and a lunch break. But for our post rider, navigating less-than-ideal roads, this one-way journey spanned a long day, stretching over 9 hours and even necessitating an overnight stay in Haverhill before returning to Boston.

If you take a gander at the map on the below, recreated using the wonders of Google Maps and keeping many of the old roads in mind (although a handful have disappeared or been divided by new highways), you'll see that this route from Haverhill to Boston is strikingly direct. This route certainly did Andover a solid favor by passing right through the Center, now North Andover, with just a few minor detours from a straightforward north-south trajectory, mostly designed to skirt around those sizable bodies of water.

Post-riders

Back in 1775, a post rider emerged to connect Boston and Haverhill, along with the establishment of a post office in Haverhill itself. This post rider held quite a prominent place in both the eyes of the public and his own. Picture this: he'd dart around on horseback, carrying important messages "post-haste," equipped with saddlebags and a trusty horn to signal his approach. Intriguingly, letters intended for the folks in Andover would often get advertised in Haverhill's post office.

Then, in 1780, the same Samuel Bean, who happened to be a post-rider, had the unique task of ferrying the "Independent Chronicle" from Boston all the way to Londonderry, NH. His advertisement in the February 17, 1780, edition of the "Chronicle" provides us a curious peek into the quirks of those times:

The shift from post riders like Samuel Bean and Paul Revere to coaches brought about significant changes, not only in terms of comfort but also in the capacity to accommodate more passengers.

EARLY COACHES: Those early coaches went by various names. Back in 1767, it was a "stage-chaise" making its rounds between Salem and Boston. Meanwhile, you had a "stage-coach" and "stage-wagon" handling shorter routes out of Boston. Come 1772, a "stage-chariot" graced the road between Boston and Marblehead. Even as early as 1773, Thomas Beals was running "Mail Stage Carriages between Boston and Providence."

Now, picture this: a description of a stage-wagon from 1795 paints quite the picture. Imagine a long car with four benches. Inside, three of these benches held a total of nine passengers, with the tenth perched next to the driver on the front bench. A lightweight roof was upheld by eight slender pillars, four on either side. Three sizeable leather curtains, suspended on the roof, could be rolled up or let down according to the passengers' whims. Now, here's the kicker – there was no designated space for luggage; everyone was expected to tuck their belongings under their seat or between their legs. To board, you'd enter from the front over the driver's bench. Naturally, the three passengers on the back seat had to maneuver their way across all the other benches to reach their spots. Oh, and those benches? They lacked backs, which made for quite the challenging journey, especially on poorly constructed roads. I don't think I will ever complain about a tight airline seat again!

STAGECOACH: Flash forward to 1781, and a stage was making the rounds from Boston to Portsmouth (and beyond to Portland), passing through Andover, Haverhill, and venturing into New Hampshire via Exeter before finally reaching Portsmouth. This route was direct, and, thanks to early well-built roads, it evolved into a highway of its time. This made it a bustling thoroughfare, especially with trips to Haverhill, Londonderry, and Portsmouth. Most stops along the way hosted two trips per week and given the impressive volume of cider being consumed (yes, that's a key historical detail), one can imagine that this tavern was frequented by a considerable number of passengers. Each stage was designed to hold nine passengers plus a driver. If you do the math and consider the possibility of daily stages, that could mean more than 20 visitors passing through the tavern in a single day (with 1-2 stages in each direction daily), not to mention additional patrons of the establishment. Quite the lively hub, I'd say!

In upcoming issues, we will talk about the living taverns of downtown Andover and their impact on the citizens and the events of the day.

Sources

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1880.

Earle, Alice Morse, Stage Coach and Tavern Days, The MacMillan Company, London, 1900.

Forbes, Allan and Ralph M. Eastman, Taverns and Stagecoaches of New England, Vol I and II, State Street Trust Company, Boston 1954.

Holbrook, Stewart H., The Old Poft Road: The Story of the Boston Post Road, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. New York, 1962.

Comments ()