The Forgotten Taste of Cider

I have always had a fondness for cider, especially hard cider. However, it wasn't until my travels in Europe, particularly in the UK and France, that I truly discovered the exquisite flavors that cider can offer. I found that cider, when crafted with precision, can resemble a dry white wine. This led me to question why American cider is often more akin to a sweet soda. What was the taste of early Americans, and how did it disappear over time? Let's delve into the rich history of cider and uncover the answers.

Cider in old England

Wine and beer are widely recognized as ancient drinks, with their origins dating back to the time of the Egyptians. Made from various ingredients such as grains, fruits, vegetables, and plants, these beverages have become ubiquitous across the globe. However, cider, being primarily derived from apples grown in temperate zones, has a more localized presence.

When the Romans invaded England in 55 BC, they encountered cider as a popular drink. By the 3rd century, cider had gained widespread popularity in Europe, surpassing even beer in terms of consumption by the 11th century. Throughout history, cider was cherished by monks, and it was even referenced by Shakespeare in "A Midsummer Night's Dream."

In England, there were over 350 varieties of apples used in cider production, boasting names like Hangdown’s, Old Foxwhelp, Golden Ball, Golden Pippins, Lady’s Finger, and Sheep’s Nose. Hard cider was a popular rural drink, known for its affordability and 7% alcohol content, making it as potent as beer.

The Early Days of American Cider

By 1623, apple trees were being planted in the Massachusetts Bay Colony by William Blaxton, a dissenting Church of England clergyman. In 1635, Blaxton ran afoul of British authorities and moved to Rhode Island, where he started his first orchard and created the first American apple variety, Blaxton’s Yellow Sweeting. Others suggest that the Roxbury Russett, found in Roxbury, Massachusetts in 1647, might have been the first American variety.

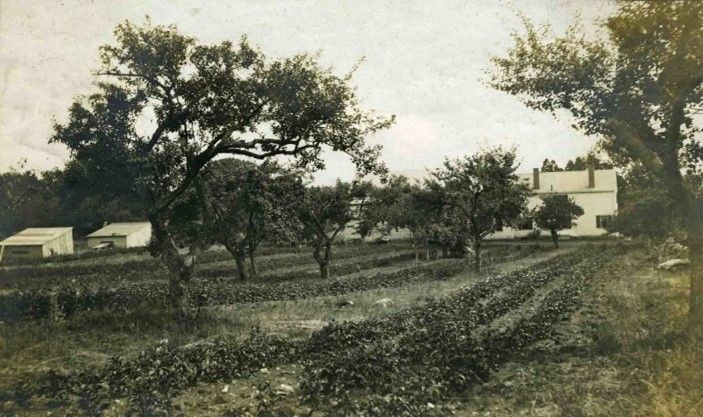

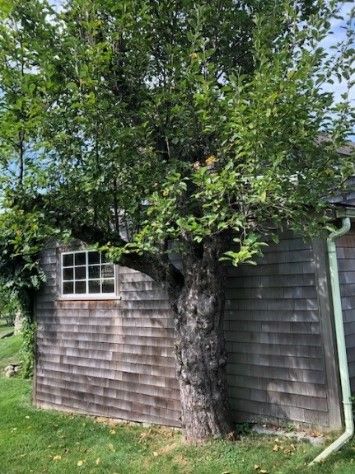

Roxbury, the same town where the Chandlers (and our future Tavernkeeper) settled in 1637, was well-known for its apple orchards. However, the orchards of the 1600s were quite different from the neat and orderly orchards we see today. Farmers would spread pomace (the leftover seeds, skins, etc. from cider pressing) onto their fields and allow the trees to grow wherever they sprouted. Each tree could look distinct as grafting wasn't prevalent, and their heights often exceeded 25 feet. In my mind, I picture a field filled with trees of various sizes, scattered haphazardly, while sheep mow the grass and provide additional fertilizer.

A single apple tree could yield bushels of apples, enough to produce 5 or 6 barrels of cider. Farmers would plant apple trees wherever they could grow. Grafted apples were introduced as early as 1647, but most farmers started their apple trees from seeds. In 1650, a bushel of apples sold for 6-8 shillings, which was equivalent to 15.8 d/gallon.

In 1726, a report indicated that a town of 40 families near Boston put up nearly 3,000 barrels (~96,000 gallons) of cider. Towns kept track of the amount produced and, in many cases, used it as a point of pride.

Cider mills could be found on many farms alongside the apple orchards. This common drink graced the table at every meal and was carried into the fields to quench thirst. Drawing cider for the day was a task given to the younger members of the household, though it wasn't a particularly enjoyable chore. Rules were established, such as the last one out of bed having to draw the cider for the day. Cider was drawn in small quantities as it was not considered suitable to drink once it became warm. Any good cider left at the end of the day was emptied into a barrel kept for leftovers, quickly transforming into cider vinegar.

By 1775, it is estimated that one out of every ten homes in New England had a cider press. This highlights the widespread prevalence and significance of cider in the region.

And they drank a lot of cider

During colonial times, colonists had a peculiar aversion to drinking water, which led them to embrace cider as an inexpensive alternative. Cider became a staple morning drink in the countryside, enjoyed with breakfast, as well as a popular choice in taverns and inns frequented by travelers. Interestingly, even students at Harvard College were served cider with their meals. Children, too, were not excluded from this cider culture. They were given diluted cider, commonly referred to as "water-cider" or "ciderkin." This beverage was made by soaking the leftover pomace from cider pressing in water and then pressing it again.

In households, it was common to have a cider container, often made of pottery, placed in the center of the table. Each family member had their designated spot on the container from which they would drink, adding a sense of conviviality to the dining experience.

In 1761, a Topfield will stated that the widow Sarah Cummings should be supplied annually with five (5) barrels of cider, which roughly amounts to 7 cups of cider per day. By 1767, one historian reported that in Massachusetts, the per capita average was 1.14 barrels of cider, equivalent to 35 gallons per person. This estimate is likely accurate, considering the average family unit consisted of around 5 people or more. Even John Adams, our second president, believed in the health benefits of hard cider and consumed a tankard of it every morning. (A tankard typically holds a quart or more, so if that was all John Adams drank, he consumed approximately 90+ gallons or 3 barrels annually).

The popularity of cider extended beyond mere consumption. It became a form of exchange and bartering, used as a means of payment for services rendered. Doctors, schoolteachers, and ministers would accept cider as a form of compensation. In fact, historical records reveal that some ministers had a quota of 40 barrels of cider for the winter, emphasizing its integral role in daily life. In 17th-century Boston tap houses, an "ale-quart of cyder spiced and sweetened with sugar for a goat" could be obtained for approximately fourpence. By 1740, a barrel of cider was sold for three shillings.

Cider production and consumption truly permeated the colonial society, leaving a lasting imprint on New England's cultural fabric.

The decline (and lost flavors) of Cider

In 1790, a staggering 96% of Americans called the farm their home. By 1860, the percentage of people residing on farms had dipped to 86%, and a mere half a century later, that number plummeted to a mere 30%. This significant shift in demographics marked a turning point in American history.

The tradition of cider making was deeply intertwined with farm life. But with the aftermath of the Civil War, countless orchards fell into disrepair and were abandoned. To compound matters, shifting preferences and the rise of the Temperance movement further impacted cider orchards. Probation brought the end to the remaining cider orchards in the United States. As a result, many magnificent cider-making apple varieties were lost forever.

The apples used for cider were distinct from the sweet, juicy eating apples we enjoy today. True cider apples possessed bitterness and astringency, owing to the tannins present in their skin and flesh. Tannins, also found in wine grapes, acted as stabilizers and contributed to the body and dry finish of cider. Sadly, many orchards were lost, along with the authentic taste of these ciders.

While we may never know precisely how old-time cider tasted, we can turn to English and French ciders made from traditional apple and pear varieties as a proxy. These countries, unaffected by the Temperance movement, have retained the tree varieties necessary for making great cider. These ciders are more like a fine, dry white wine versus the sweet cider sold in today’s markets in the United States.

While the golden era of cider making may have faded, its legacy continues to be cherished by those who appreciate its rich history and unique flavors. Today, efforts are being made to revive forgotten apple varieties and rediscover the lost art of traditional cider making. By honoring the past, we can ensure that the unique heritage of cider making remains alive and vibrant for future generations to savor.

Comments ()